On Grieving and Grandparents

Over the past three and a half years, the three biological grandparents that I’ve had any sort of relationship have died. These have been my first real experiences with death, apart from pets and distant relatives. Through these experiences, I have begun to push back against what we’re taught about grieving, that it is a sad and private process. Instead, I have learned that grief, at least my grief, is best experienced as a communal and celebratory affair.

– – –

My paternal grandmother, Alice Hynes, died suddenly and tragically in a car crash during Hurricane Sandy on October 30, 2012. I barely knew her and hadn’t seen her for five years before she died. I was dating a wonderful man at the time, who held me and consoled me, but apart from him and my family the only people I told were two classmates over the phone. “It’s strange, this disconnect,” I wrote in my journal that night.

I couldn’t attend her funeral because of another storm, and I struggled for years with how to grieve for her. I attempted to start a song back in 2012, and the line “Can you cry for a woman that you barely knew?” circled through my head every time I thought of her. For three years, right around Halloween, I felt an inexplicable weight on my heart. Inexplicable, at least, until I saw some post or another from my father memorializing his mother and realized that the grief I had never figured out how to express was still there, still waiting.

This fall, as the anniversary rolled around for the third time, I finally sat down to write the song that had been swirling around in my head for three years. I realized that my first question, the line that had been haunting me, was holding me back from expressing what I needed to. So instead, I wrote Granny Squares.

I’ve got a basket of granny squares that are half finished.

And I seem to remember packages on Christmas.

I was told she liked to use her hands,

I was told that she would understand,

The projects I leave strewn about the house.

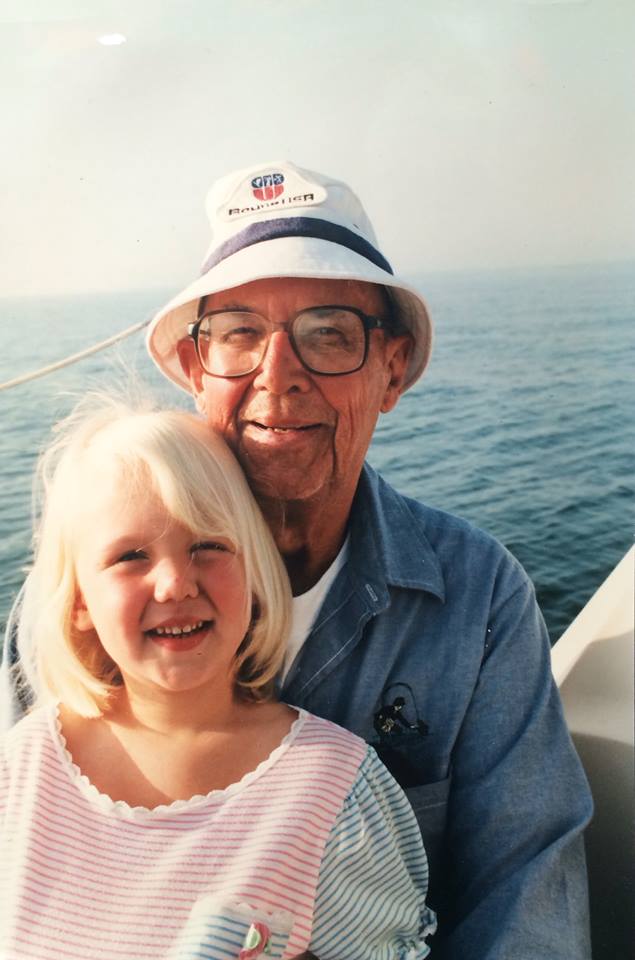

Part of what made it finally possible for me to process my grief for Grammy Hynes was the death of my maternal grandfather, Paul Darnton, on December 18, 2014. Out of all my grandparents, he was the one I had developed the closest bond with, passed down from a strong bond he had with my mother. I called him nearly once a week for the last three years of his life, which coincided with the first three years of my adult life. In my memorial to him, I wrote that “we provided each other with irreplaceable windows into distant worlds.” He saw a version of my generation that wasn’t condemnation from mass media, and I saw a personal story of WWII and the surrounding history.

His was a graceful death, at his home, surrounded by his children. My mother, his youngest daughter, was the last with him and she held his hand as he died in the middle of the night. She called me the next morning, and though I had known it was coming, the reality hit me like a battering ram. I called out of work and spent the day alone in bed, buying my plane ticket to the funeral and looking at old photographs. This picture of him, posted with my memorial, received an incredibly supportive and positive response from social media, reminding me that there are many ways to be connected with people. For all the slack social media gets, each new like brought me great comfort as I grieved for the man who taught me the definition of unconditional love.

His was a graceful death, at his home, surrounded by his children. My mother, his youngest daughter, was the last with him and she held his hand as he died in the middle of the night. She called me the next morning, and though I had known it was coming, the reality hit me like a battering ram. I called out of work and spent the day alone in bed, buying my plane ticket to the funeral and looking at old photographs. This picture of him, posted with my memorial, received an incredibly supportive and positive response from social media, reminding me that there are many ways to be connected with people. For all the slack social media gets, each new like brought me great comfort as I grieved for the man who taught me the definition of unconditional love.

Again, I called a friend and spoke on the phone, I even talked in person to one of my roommates, but I didn’t have the courage or the awareness to ask them for what I really needed: a person to sit down and hold me as the emotions washed through. Thankfully, I got on a plane to Michigan the next day and spent the following week surrounded by family, memories, and love. I learned, in that time, that the best way to grieve is to express love. For those who have died, for those who are still here, for yourself.

I recently read Tuesdays with Morrie for the first time, unaware of how apt it would soon be for my life:

‘Everybody knows they’re going to die, but nobody believes it. If we did, we would do things differently,’ Morrie said. ‘So we kid ourselves about death,’ I said. ‘Yes, but there’s a better approach. To know you’re going to die and be prepared for it at any time. That’s better. That way you can be actually be more involved in your life while you’re living. . . Every day, have a little bird on your shoulder that asks, ‘Is today the day? Am I ready? Am I doing all I need to do? Am I being the person I want to be?… The truth is, Mitch, once you learn how to die, you learn how to live… Most of us walk around as if we’re sleepwalking. We really don’t experience the world fully because we’re half asleep, doing things we automatically think we have to do… Learn how to die, and you learn how to live.’ – Tuesdays with Morrie

This book made me start to think about how I want to die and in turn about how I want to live. I had a new song flirting with my mind on just this topic, waiting for me to have the time to pay attention to it, when I got the call from my mother that Grandma had taken a turn for the worse. In the haze that follows such a phone call, I sat down and wrote When I Die, consciously choosing to start the grieving process before it began. It is, in my opinion, a celebratory song as I hope my death will be a celebrated death.

Yesterday, I started the process for the third time in as many years following the death of my maternal grandmother, Jeane Darnton. But this time, I finally knew what to do with my grief. Instead of running from it or being laid flat by it, I welcomed it with open arms. I sang my new song to myself, thinking of my grandmother in the way I hope people will think of me when I die: with love for the time she had rather than anger at the time we no longer have.

Yesterday, I started the process for the third time in as many years following the death of my maternal grandmother, Jeane Darnton. But this time, I finally knew what to do with my grief. Instead of running from it or being laid flat by it, I welcomed it with open arms. I sang my new song to myself, thinking of my grandmother in the way I hope people will think of me when I die: with love for the time she had rather than anger at the time we no longer have.

Instead of stoically going on with my day, I reached out. I told my co-worker, who embraced me, and called my friend, who rallied me. When the work day was over, I debated about whether to go to the Hearth’s monthly waltzing night. Was my grief appropriate for a night of dancing and music? Or would it be better to keep that weight for myself? But as I was thinking, a line from my song kept running through my head: “When I die, I hope you’ll dance to the sunrise to see how alive you are. Dance so much, your heart beats fast enough to beat for both of us.”

And so I finally found the courage to ask for companionship while I grieved. My heart was pounding as I walked through the door, afraid that I was just going to have to put on a front and smile while I wanted to cry. But the warmth that met me, even without knowing what I carried, steadied me. I danced for my grandmother in the arms of both friends and strangers. I smiled and I laughed and at the end I cried, and my community held me.

Though I was afraid to expose my grief, afraid that it was inappropriate and would dampen the night, I realized that grief is not a sad thing. Grief is a loving thing. It is, in its best form, a celebration of a life well spent and thus much missed. So often we think it is better to take our grief home with us, not to let it impact other people, but I cannot think of a better place to experience grief than in the arms of people who love you.

I am humbled and grateful for the warmth I received from the Hearth last night, and for the response I received on social media from my community when I shared this story. I only hope that the Hearth dances in celebration the day I die, the way I danced for Grandma.

– – –