Review: Parable of the Sower

-written by Hearth Member, Marika McCoola

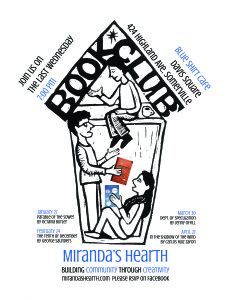

On Wednesday, three of us met at The Blue Shirt Cafe to discuss Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. I’d selected the book based on rave reviews I’d heard from others. I was also interested in the book from a historical viewpoint. It’s a post-apocalyptic novel written by a black woman and published in 1993. In the past decade, a number of dystopian and post-apocalyptic novels have been published (there is a difference between the two, but we’ll not get into that right now) and discussions of diversity in publishing are very much in public conversation.

When I brought up the pub date, it seemed to account for what was bothering people about the book. The first half of the book sets up daily life and the community the protagonist, Lauren, lives in, a self-gated community headed by Lauren’s Reverend father. This portion of the book, spanning a number of years, feels slow. It’s narrated in the first person by Lauren, who is 14 at the start. As one person noted, “I would’ve liked this if I’d read it at 14, but not now.” I think this is true not just relating to age, but also true in terms of what one’s read since then. The current dystopias and post-apocalyptic novels are extremely fast paced, with very tight plotting (often YA fare, which seeks to hold the attention of reluctant readers) and therefore one’s expectations for the book aren’t immediately met.

This section was, however, of interest in terms of the conversations Lauren had with her father, the Reverend, on how to inspire and handle a community. How can one inspire and convince a community without using fear, which can often backfire? Miranda, in particular, found this of interest. It’s also interesting in that it introduces us to Lauren, who has hyper-empathy, and her diverse family (black and hispanic). We wondered, though, if the length of this section was necessary, or if everything could’ve been established in half of the space.

This section was, however, of interest in terms of the conversations Lauren had with her father, the Reverend, on how to inspire and handle a community. How can one inspire and convince a community without using fear, which can often backfire? Miranda, in particular, found this of interest. It’s also interesting in that it introduces us to Lauren, who has hyper-empathy, and her diverse family (black and hispanic). We wondered, though, if the length of this section was necessary, or if everything could’ve been established in half of the space.

In the second half of the book, set outside the community, there’s a lot of graphic detail in terms of the brutality occurring. After reading Station 11, in which the really terrible years aren’t covered, this feels even more graphic. The question was raised, were some graphic details included as a way of proving that female writers aren’t scared to include the necessary details? I don’t feel I’ve done enough research on the history of the sub-genre (particularly as it pertains to the adult market) to comment on this, but it would be interesting to peruse.

From a historical perspective, I think Parable of the Sower is an important read, especially if considered in conversation with current trends in post-apocalyptic novels and character diversity in science-fiction; they’re conversations I’d very much like to continue having.

February’s pick is The Tenth of December by George Saunders, a book of short stories. If you don’t have time to read all the stories, read a selection and come and discuss your picks with us!